Information theory

Information Content

Given a random variable $X$ and a possible outcome $x_i$ associated with a probability $p_X(x_i)=p_i$, the information content (also called self-information or surprisal) is defined as :

\[\operatorname{I} (p_i) = - log(p_i)\]![]() Intuition : The "information" of an event is higher when the event is less probable. Indeed, if an event is not surprising, then learning about it does not convey much additional information.

Intuition : The "information" of an event is higher when the event is less probable. Indeed, if an event is not surprising, then learning about it does not convey much additional information.

![]() Example : "it is currently cold in Antarctica" does not convey much information as you knew it with high probability. "It is currently very warm in Antarctica" carries a lot more information and you would be surprised about it.

Example : "it is currently cold in Antarctica" does not convey much information as you knew it with high probability. "It is currently very warm in Antarctica" carries a lot more information and you would be surprised about it.

![]() Side note :

Side note :

- $\operatorname{I} (p_i) \in [0,\infty[$

- Don't confuse the information content in information theory with the everyday word which refers to "meaningful information". A book with random letters will have more information content because each new letter would be a surprise to you. But it will definitely not have more meaning than a book with English words .

Entropy

Long Story Short

![]() Intuition :

Intuition :

- The entropy of a random variable is the expected information-content. I.e. the expected amount of surprise you would have by observing a random variable .

- Entropy is the expected number of bits (assuming $log_2$) used to encode an observation from a (discrete) random variable under the optimal coding scheme .

![]() Side notes :

Side notes :

- $H(X) \geq 0$

- Entropy is maximized when all events occur with uniform probability. If $X$ can take $n$ values then : $max(H) = H(X_{uniform})= \sum_i^K \frac{1}{K} \log(\frac{1}{ 1/K} ) = \log(K)$

Long Story Long

The concept of entropy is central in both thermodynamics and information theory, and I find that quite amazing. It originally comes from statistical thermodynamics and is so important, that it is carved on Ludwig Boltzmann's grave (one of the father of this field). You will often hear:

- Thermodynamics: Entropy is a measure of disorder

- Information Theory: Entropy is a measure of information

These 2 way of thinking may seem different but in reality they are exactly the same. They essentially answer: how hard is it to describe this thing?

I will focus here on the information theory point of view, because its interpretation is more intuitive for machine learning. I also don't want to spend to much time thinking about thermodynamics, as people that do often commit suicide ![]() .

.

In information theory there are 2 intuitive way of thinking of entropy. These are best explained through an example :

![]() Suppose my friend Claude offers me to join him for a NBA game (Cavaliers vs Spurs) tonight. Unfortunately I can't come, but I ask him to record who scored each field goals. Claude is very geeky and uses a binary phone which can only write 0 and 1. As he doesn't have much memory left, he wants to use the smallest possible number of bits.

Suppose my friend Claude offers me to join him for a NBA game (Cavaliers vs Spurs) tonight. Unfortunately I can't come, but I ask him to record who scored each field goals. Claude is very geeky and uses a binary phone which can only write 0 and 1. As he doesn't have much memory left, he wants to use the smallest possible number of bits.

- From previous games, Claude knows that Lebron James will very likely score more than the old (but awesome

) Manu Ginobili. Will he use the same number of bits to indicate that Lebron scored, than he will for Ginobili ? Of course not, he will allocate less bits for Lebron's buckets as he will be writing them down more often. He's essentially exploiting his knowledge about the distribution of field goals to reduce the expected number of bits to write down. It turns out that if he knew the probability $p_i$ of each player $i$ to score, he should encode their name with $nBit(p_i)=\log_2(1/p_i)$ bits. This has been intuitively constructed by Claude (Shannon) himself as it is the only measure (up to a constant) that satisfies axioms of information measure. The intuition behind this is the following:

) Manu Ginobili. Will he use the same number of bits to indicate that Lebron scored, than he will for Ginobili ? Of course not, he will allocate less bits for Lebron's buckets as he will be writing them down more often. He's essentially exploiting his knowledge about the distribution of field goals to reduce the expected number of bits to write down. It turns out that if he knew the probability $p_i$ of each player $i$ to score, he should encode their name with $nBit(p_i)=\log_2(1/p_i)$ bits. This has been intuitively constructed by Claude (Shannon) himself as it is the only measure (up to a constant) that satisfies axioms of information measure. The intuition behind this is the following:- Multiplying probabilities of 2 players scoring should result in adding their bits. Indeed imagine Lebron and Ginobili have respectively 0.25 and 0.0625 probability of scoring the next field goal. Then, the probability that Lebron scores the 2 next field goals would be the same than Ginobili scoring a single one ($p(Lebron)*p(Lebron) = 0.25 * 0.25 = 0.0625 = Ginobili$). We should thus allocate 2 times less bits for Lebron, so that on average we always add the same number of bits per observation. $nBit(Lebron) = \frac{1}{2} * nBit(Ginobili) = \frac{1}{2} * nBit(p(Lebron)^2)$. The logarithm is a function that turns multiplication into sums as required. The number of bits should thus be of the form $nBit(p_i) = \alpha * \log(p_i) + \beta $

- Players that have higher probability of scoring should be encoded by a lower number of bits . I.e $nBit$ should decrease when $p_i$ increases: $nBit(p_i) = - \alpha * \log(p_i) + \beta, \alpha > 0 $

- If Lebron had $100%$ probability of scoring, why would I have bothered asking Claude to write anything down ? I would have known everything a priori . I.e $nBit$ should be $0$ for $p_i = 1$ : $nBit(p_i) = \alpha * \log(p_i), \alpha > 0 $

- Now Claude sends me the message containing information about who scored each bucket. Seeing that Lebron scored will surprise me less than Ginobili. I.e Claude's message gives me more information when telling me that Ginobili scored. If I wanted to quantify my surprise for each field goal, I should make a measure that satisfies the following conditions:

- The lower the probability of a player to score, the more surprised I will be . The measure of surprise should thus be a decreasing function of probability: $surprise(x_i) = -f(p_i) * \alpha, \alpha > 0$.

- Supposing that players scoring are independent of one another, it's reasonable to ask that my surprise seeing Lebron and Ginobili scoring in a row should be the same than the sum of my surprise seeing that Lebron scored and my surprise seeing that Ginobili scored. I.e. Multiplying independent probabilities should sum the surprise : $surprise(p_i * x_j) = surprise(p_i) + surprise(p_j)$.

- Finally, the measure should be continuous given probabilities . $surprise(p_i) = -\log(p_{i}) * \alpha, \alpha > 0$

Taking $\alpha = 1 $ for simplicity, we get $surprise(p_i) = -log(p_i) = nBit(p_i)$. We thus derived a formula for computing the surprise associated with event $x_i$ and the optimal number of bits that should be used to encode that event. This value is called information content $I(p_i)$. In order to get the average surprise / number of bits associated with a random variable $X$ we simply have to take the expectation over all possible events (i.e average weighted by probability of event). This gives us the entropy formula $H(X) = \sum_i p_i \ \log(\frac{1}{p_i}) = - \sum_i p_i\ log(p_i)$

From the example above we see that entropy corresponds to :

- to the expected number of bits to optimally encode a message

- the average amount of information gained by observing a random variable

![]() Side notes :

Side notes :

- From our derivation we see that the function is defined up to a constant term $\alpha$. This is the reason why the formula works equally well for any logarithmic base, indeed changing the base is the same as multiplying by a constant. In the context of information theory we use $\log_2$.

- Entropy is the reason (second law of thermodynamics) why putting an ice cube in your Moscow Mule (my go-to drink) doesn't normally make your ice cube colder and your cocktail warmer. I say "normally" because it is possible but very improbable : ponder about this next time your sipping your own go-to drink

!

!

![]() Resources : Excellent explanation of the link between entropy in thermodynamics and information theory, friendly introduction to entropy related concepts

Resources : Excellent explanation of the link between entropy in thermodynamics and information theory, friendly introduction to entropy related concepts

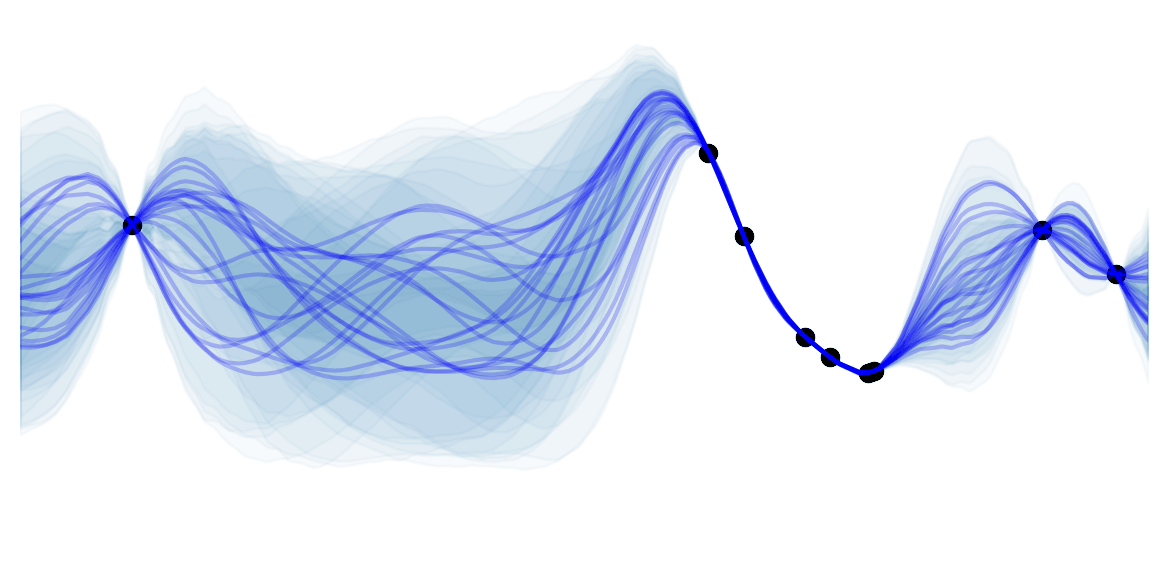

Differential Entropy

Differential entropy (= continuous entropy), is the generalization of entropy for continuous random variables.

Given a continuous random variable $X$ with a probability density function $f(x)$:

\[h(X) = h(f) := - \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) \log {f(x)} \ dx\]If you had to make a guess, which distribution maximizes entropy for a given variance ? You guessed it : it's the Gaussian distribution.

![]() Side notes : Differential entropy can be negative.

Side notes : Differential entropy can be negative.

Cross Entropy

We saw that entropy is the expected number of bits used to encode an observation of $X$ under the optimal coding scheme. In contrast cross entropy is the expected number of bits to encode an observation of $X$ under the wrong coding scheme. Let's call $q$ the wrong probability distribution that is used to make a coding scheme. Then we will use $-log(q_i)$ bits to encode the $i^{th}$ possible values of $X$. Although we are using $q$ as a wrong probability distribution, the observations will still be distributed based on $p$. We thus have to take the expected value over $p$ :

\[H(p,q) = \mathbb{E}_p\left[\operatorname{I} (q_i)\right] = - \sum_i p_i \log(q_i)\]From this interpretation it naturally follows that:

- $H(p,q) > H(p), \forall q \neq p$

- $H(p,p) = H(p)$

![]() Side notes : Log loss is often called cross entropy loss, indeed it is the cross-entropy between the distribution of the true labels and the predictions.

Side notes : Log loss is often called cross entropy loss, indeed it is the cross-entropy between the distribution of the true labels and the predictions.

Kullback-Leibler Divergence

The Kullback-Leibler Divergence (= relative entropy = information gain) from $q$ to $p$ is simply the difference between the cross entropy and the entropy:

\[\begin{align*} D_{KL}(p\|q) &= H(p,q) - H(p) \\ &= [- \sum_i p_i \log(q_i)] - [- \sum_i p_i \log(p_i)] \\ &= \sum_i p_i \log(\frac{p_i}{q_i}) \end{align*}\]![]() Intuition

Intuition

- KL divergence corresponds to the number of additional bits you will have to use when using an encoding scheme based on the wrong probability distribution $q$ compared to the real $p$ .

- KL divergence says in average how much more surprised you will be by rolling a loaded dice but thinking it's fair, compared to the surprise of knowing that it's loaded.

- KL divergence is often called the information gain achieved by using $p$ instead of $q$

- KL divergence can be thought as the "distance" between 2 probability distribution. Mathematically it's not a distance as it's none symmetrical. It is thus more correct to say that it is a measure of how a probability distribution $q$ diverges from an other one $p$.

KL divergence is often used with probability distribution of continuous random variables. In this case the expectation involves integrals:

\[D_{KL}(p \parallel q) = \int_{- \infty}^{\infty} p(x) \log(\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}) dx\]In order to understand why KL divergence is not symmetrical, it is useful to think of a simple example of a dice and a coin (let's indicate head and tails by 0 and 1 respectively). Both are fair and thus their PDF is uniform. Their entropy is trivially: $H(p_{coin})=log(2)$ and $H(p_{dice})=log(6)$. Let's first consider $D_{KL}(p_{coin} \parallel p_{dice})$. The 2 possible events of $X_{dice}$ are 0,1 which are also possible for the coin. The average number of bits to encode a coin observation under the dice encoding, will thus simply be $log(6)$, and the KL divergence is of $log(6)-log(2)$ additional bits. Now let's consider the problem the other way around: $D_{KL}(p_{dice} \parallel p_{coin})$. We will use $log(2)=1$ bit to encode the events of 0 and 1. But how many bits will we use to encode $3,4,5,6$ ? Well the optimal encoding for the dice doesn't have any encoding for these as they will never happen in his world. The KL divergence is thus not defined (division by 0). The KL divergence is thus not symmetric and cannot be a distance.

![]() Side notes : Minimizing cross entropy with respect to $q$ is the same as minimizing $D_{KL}(p \parallel q)$. Indeed the 2 equations are equivalent up to an additive constant (the entropy of $p$) which doesn't depend on $q$.

Side notes : Minimizing cross entropy with respect to $q$ is the same as minimizing $D_{KL}(p \parallel q)$. Indeed the 2 equations are equivalent up to an additive constant (the entropy of $p$) which doesn't depend on $q$.

Mutual Information

\[\begin{align*} \operatorname{I} (X;Y) = \operatorname{I} (Y;X) &:= D_\text{KL}\left(p(x, y) \parallel p(x)p(y)\right) \\ &= \sum_{y \in \mathcal Y} \sum_{x \in \mathcal X} { p(x,y) \log{ \left(\frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)\,p(y)} \right) }} \end{align*}\]![]() Intuition : The mutual information between 2 random variables X and Y measures how much (on average) information about one of the r.v. you receive by knowing the value of the other. If $X,\ Y$ are independent, then knowing $X$ doesn't give information about $Y$ so $\operatorname{I} (X;Y)=0$ because $p(x,y)=p(x)p(y)$. The maximum information you can get about $Y$ from $X$ is all the information of $Y$ i.e. $H(Y)$. This is the case for $X=Y$ : $\operatorname{I} (Y;Y)= \sum_{y \in \mathcal Y} p(y) \log{ \left(\frac{p(y)}{p(y)\,p(y)} \right) = H(Y) }$

Intuition : The mutual information between 2 random variables X and Y measures how much (on average) information about one of the r.v. you receive by knowing the value of the other. If $X,\ Y$ are independent, then knowing $X$ doesn't give information about $Y$ so $\operatorname{I} (X;Y)=0$ because $p(x,y)=p(x)p(y)$. The maximum information you can get about $Y$ from $X$ is all the information of $Y$ i.e. $H(Y)$. This is the case for $X=Y$ : $\operatorname{I} (Y;Y)= \sum_{y \in \mathcal Y} p(y) \log{ \left(\frac{p(y)}{p(y)\,p(y)} \right) = H(Y) }$

![]() Side note :

Side note :

- The mutual information is more similar to the concept of entropy than to information content. Indeed, the latter was only defined for an outcome of a random variable, while the entropy and mutual information are defined for a r.v. by taking an expectation.

- $\operatorname{I} (X;Y) \in [0, min(\operatorname{I} (X), \operatorname{I} (Y;Y))]$

- $\operatorname{I} (X;X) = \operatorname{I} (X)$

- $\operatorname{I} (X;Y) = 0 \iff X \,\bot\, Y$

- The generalization of mutual information to $V$ random variables $X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_V$ is the Total Correlation: $C(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_V) := \operatorname{D_{KL}}\left[ p(X_1, \dots, X_V) \parallel p(X_1)p(X_2)\dots p(X_V)\right]$. It denotes the total amount of information shared across the entire set of random variables. The minimum $C_\min=0$ when no r.v. are statistically dependent. The maximum total correlation occurs when a single r.v. determines all the others : $C_\max = \sum_{i=1}^V H(X_i)-\max\limits_{X_i}H(X_i)$.

- Data Processing Inequality: for any Markov chain $X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z$: $\operatorname{I} (X;Y) \geq \operatorname{I} (X;Z)$

- Reparametrization Invariance: for invertible functions $\phi,\psi$: $\operatorname{I} (X;Y) = \operatorname{I} (\phi(X);\psi(Y))$

Machine Learning and Entropy

This is all interesting, but why are we talking about information theory concepts in machine learning ![]() ? Well it turns our that many ML algorithms can be interpreted with entropy related concepts.

? Well it turns our that many ML algorithms can be interpreted with entropy related concepts.

The 3 major ways we see entropy in machine learning are through:

-

Maximizing information gain (i.e entropy) at each step of our algorithm. Example:

- When building decision trees you greedily select to split on the attribute which maximizes information gain (i.e the difference of entropy before and after the split). Intuitively you want to know the value of the attribute, that decreases the randomness in your data by the largest amount.

-

Minimizing KL divergence between the actual unknown probability distribution of observations $p$ and the predicted one $q$. Example:

- The Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) of our parameters $\hat{ \theta }_{MLE}$ are also the parameter which minimizes the KL divergence between our predicted distribution $q_\theta$ and the actual unknown one $p$ (or the cross entropy). I.e

-

Minimizing KL divergence between the computationally intractable $p$ and a simpler approximation $q$. Indeed machine learning is not only about theory but also about how to make something work in practice.Example:

- This is the whole point of Variational Inference (= variational Bayes) which approximates posterior probabilities of unobserved variables that are often intractable due to the integral in the denominator. Thus turning the inference problem to an optimization one. These methods are an alternative to Monte Carlo sampling methods for inference (e.g. Gibbs Sampling). In general sampling methods are slower but asymptotically exact.